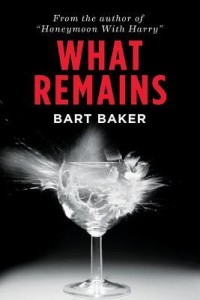

About the Book, What Remains:

When Conner Carter is banished from New York for cheating on his socialite wife, he flies across country to Sonoma, California to stay with his brother Cody, Cody’s ridiculously wealthy husband, Rhett, and their two adopted Cambodian children. Since childhood, Conner has been jealous of the gilded life Cody has led, but Conner learns that what glitters often tarnishes and shatters in shocking and dangerous ways. Having always taken life’s easiest route, Conner now finds that path closed when he is forced to step up for his brother when Cody’s personal life crumbles after Rhett goes missing in Colombia on a documentary film shoot. Conner’s world unravels when the woman he’s fallen in love with, their black Puerto Rican nanny, Zinzi, finds her violent past catching up with her. From the tattered and surprising pieces of these characters’ intense and complicated lives, these people will discover the strength in What Remains.

Buy a copy from Amazon

About the Author, Bart Baker:

With two feature films, eleven movies for television, four television series credits, as well as eight theatrical plays produced around the world, What Remains is Bart’s second novel. Bart’s first novel, Honeymoon with HarryHONEYMOON WITH HARRY, was a critical and commercial success and the movie rights were bought by Warner Bros./New Line Cinema for a feature film. He’s recently sold a film project in conjunction with the hit song by Miranda Lambert, OVER YOU, to the Lifetime Network. Bart lives in Ellisville, Missouri with his family.

Connect with Bart:

Website: BartBaker.com

Goodreads: What Remains

Read the first chapter of What Remains, by Bart Baker:

CONNER

“Do I know you?” I asked, casually flirting as I shook the hand of the outstanding brunette in the Versace cocktail dress. It’s a skill I’ve perfected for these opaque charity fundraisers I get bullied into attending.

“We slept together two years ago,” she stated with a razor’s edge etched into her voice. “You never called.”

Not the best statement to make when I’m standing with my wife of three years.

Now before you cast stones, it’s not like I was the only one cheating throughout our marriage. She had her dalliances with men far more successful than I, men she gravitated towards once we were married as if to show me what she hoped I’d become while simultaneously reminding me that I never would. I possessed no natural status of my own.

Any cachet I owned, I married into.

Prior to the “I do’s” there were only a few trinkets in my bag of tricks: a chameleon-like ability to be all things to all people, a well-honed smile, clever patter and faux-humble charm. People liked me, especially those who didn’t dig too deeply below the surface. Those who did, only found more layers of surface.

Now, one might think that I’m being self-deprecating or modest, or that I’m pathological. None of the above. Well, there’s always that edge of pathology. Not of the Ted Bundy-variety, though we both had a fascination with women. His usually ended in death. Mine ended with less finality. But they ended.

If there has been anything consistent throughout my life, it’s my keen ability at seeming to be the perfect guy. You could bring me home to your mother and she would want to squeeze me, feed me, or sleep with me. All three have happened. But I can also watch a game with your dad and quote stats of just about any sport, though I played none at all. Most importantly, I am inventive in bed and rabbit quick with a compliment.

Before I make these qualities sound too good, anyone appearing this wonderful has flaws. Most of mine are minor. And by that I mean none are felonious. No one’s died or lost their life savings because of me. But there is one thing I’m really not proud of. Some people can overlook it because in the entire scheme of things it’s not epic, but for others it’s certainly a deal breaker. See, I have this problem with work. Not employment. I rather enjoy making money. But for the life of me I’ve never understood the fascination with hard work. I know people say that nothing in life worth having comes without some suffering. Huh? Where is this written? I know it’s not the Bible, not that I’ve read it. Nor in the Koran, not that I’ve read it either. And I’m fairly certain it’s not in the teachings of Buddha, not that I’ve heard them. I’m not sure who made up that load of crap but I can state with absolute certainty that I do not believe it to be true.

My philosophy: Nothing worth suffering over is worth the time you put into it. And its axiom: If it’s difficult, you’ll only resent it later.

I’ve floated though just fine for thirty-four years. Better than fine. Being me is nothing if not genuinely easy.

Until now. But we’ll get to that.

Prior to the overt discovery of my indiscretion, for some odd, inexplicable, reason my now ex-wife saw potential in me. “You have something that most men I know don’t have, Conner,” she would say.

What exactly that was I found out after we were married. The “something” was my ability to utterly and entirely piss off her father by marrying into his family. And her defiant act of “in your face” created the effect she so desired with him. It altered the current of her father’s attention directly towards her rather than any one of her four sisters. There was a lifelong battle among them to keep their father’s interest, as well as his money, flowing in their direction. By marrying someone without a pedigree who possessed no marketable talent other than looking handsome beside her in a society page photograph, she leapt past her sisters to the top of her father’s “to do” list.

Her father “took me under his wing” at his investment firm, with a fancy title of Vice-President In Charge of Physical Property, an amusing creation to keep me on a short leash. What that ridiculous title actually meant was if you wanted a different lamp in your office, you had to go through me. Those rented paintings from some happening gallery in SoHo that hung in our lobby, I selected them from a catalogue. Paper clips, reams of paper, note pads, yep, those went through me too. I reigned as a glorified cleric with a corner office. When actually working men and women rushed past on their way to important meetings or to grab a client’s phone call, they either smiled in amusement or scowled at the inequity. But a fat paycheck and little actual responsibility were two things I never walked away from.

My wife’s father kept us busy nightly, introducing us to clients, competitors and co-workers. She got an eyeful of men who would always be far more successful than me. Those who actually enjoyed toiling twelve to fourteen hours a day to impress their boss or pick up a larger paycheck. The more successful men she met, the more she regretted the decision to marry me for the sole purpose of making her father angry. Angry enough to drive a wedge between us, which he craftily accomplished by introducing me to many, many women. He knew me, or at least my ilk, well enough to know that it wouldn’t take long for me to stray from my vows, especially knowing that my wife was doing the exact same thing.

Father always knows best.

Returning to our Upper West Side co-op after the ill-timed response from the brunette, my ex- had what could be described as a shift in the tectonic plates in her head. She was not the least bit surprised or upset at my affair since that was an unspoken registered trademark of our relationship. What flipped her into homicidal overdrive was a far greater sin in her social circles, an unwritten law that no one dared break under penalty of banishment or death, whichever carried more stigma. My crime: I humiliated her in front of a roomful of her friends. And in fairness to her, it was more like five rooms full of friends, pseudo friends and other society types. The faux-pas shot through the Epilepsy Awareness Fundraiser like an overdose of chemo. People paired off and whispered. There were unsubtle glances in her direction, scowls in mine, hardy squeezes from her friends as they passed her, the seismic shift in conversation. It was as if this were an absolute first for anyone who lived in any building on the Upper West Side. And I have to admit, the look on her face was heartbreaking. She loved when people talked about her dress, her hair, her handbag, her trips, her family, but never about her. And right now that’s all they could talk about. They didn’t even wait until her back was turned.

Months later when we were in court and her short but slick attorney was doing his lawyerly best to drag me behind his Lexus, she wept on cue as she testified that when she grabbed the knife and tried to plunge it into my chest, she was fearing for her own safety. But she and I both know that when she yanked that kitchen knife from the butcher block there was nothing more on her mind than killing me.

Humiliation does funny things to some people.

Analyzing it now, I’m not really sure we were ever in love. Can people, who cheat throughout their marriage and then end up a few years later despising one another, have been truly in love to begin with? We had passion, sure. The knife incident was perverted evidence of that. But I have an amazing ability to mistake passion for something more potent. She and I also had amazing sex. She was a freak. The girl of my dreams. And I know I’m not alone in the loopy habit of misidentifying great sex for compatibility nor in believing self-interest is a form of character depth.

Our divorce was straightforward. She got damn near everything and I walked away with less than damn near nothing. Not that most of it wasn’t hers to begin with. And she had a pre-nup that her father demanded I sign before the marriage to prove it. But the little that was mine, she seized half. You know things are bad when your own lawyer glances at you over the top of the pre-nup and shakes his head knowing his only option is to beg for mercy where none would be granted. I was summarily fired from my junior VP position at her father’s company. Not that the firing was a big shocker, but he kicked me in the nuts by canning me just prior to the divorce so that she could lay claim to half of my severance.

“I’d keep you on if I thought you lived up to your potential,” he told me with such solemnity that for a fleeting moment I actually believed he meant his words. “But you are a great deal less of a man than you first led on, Conner,” he finished, his nasally voice tapping nails in the coffin containing the remains of my financial solvency.

“You know, John, you’d be more convincing if I didn’t have firsthand knowledge of how big of a weasel prick you are,” I replied, having zero to lose at that point.

Her father was not accustomed to being referred to as a “weasel prick,” but the fit was snuggly appropriate. His nose came to such a fine point I always thought some kid in grade school must have jammed his face into the pencil sharpener and turned the handle. John had the kind of features that looked better on a woman than a man. Thank God, because my ex-wife looked more like her father than her dour, politely-referred-to-as-

handsome, mother.

“I was going to give you a recommendation so you could land on your feet, but now you better hope no one contacts me.”

Yeah. Uh-huh. Right.

How do you know someone will screw you over in the future? They explain to you what they would have done for you if you just hadn’t angered them. And I’m amazingly adept at agitating people into a mouth-foaming fury. It almost never gets me anywhere. But I do seem to enjoy doing it because I seem to do it over and over again.

See what I mean about repeating patterns?

As I was walking out of his office he said, “Pray you never see my face again.”

Come on. You think I was going to let that one go? There’ve been very few times in my life I’ve been on the side of right. I was going to roll in this slop for a little longer.

“Which face would that be, you two-faced, rat mugged, sack of shit?”

Security escorted me roughly from the building, shoving me and my meager office belongings onto the sidewalk. When you behave like a dick you sort of expect to get shoved around every once in a while by an even bigger dick.

Walking aimlessly, my few office belongings packed so haphazardly in a cardboard box that they slammed together with every step, disinterested New Yorkers traipsed around me as if they could smell the gunpowder residue from my firing and wanted to avoid the stench. Then suddenly and for me rather scarily, I had my first true moment of self-awareness. And even if wasn’t the first, it was certainly the clearest.

I was spouseless, jobless, homeless. The trifecta at Loserhill Downs. And I didn’t have an easy clue as to what I was going to do next. I had shot my wad and shot myself in the foot simultaneously.

No easy task.

Now let me explain something here so that you’ll fully grasp how completely stupid what I was about to do was. See, even though I’ve never sweated much in life, it doesn’t mean I haven’t been successful. At the jobs I’ve had, I’ve always made quotas, closed deals, picked up healthy quarterly bonuses. I’ve slept with beautiful women, traveled the world (usually on someone else’s dime) and had plenty of laughs with the people I thought were my friends. But at one thing in particular I’ve been outrageously gifted: avoiding self-examination. Frankly, I find that to be a considerable waste of time. Besides being redundant, been there, lived that, it can only lead to one thing: regret. Even if you’ve had the greatest life imaginable, when you peer back at your past what comes whipping into your face like Medea’s angry locks are all the failures you’ve amassed during your tenure on the planet. Staring at your foggy-morning pile-up of private catastrophes creates a searing remorse which sinks you into a big, swirling, pisshole of despair. The final outcome: a receding hairline, ulcers, and a reputation among your friends as a whiny pain in the ass.

I’ve grown fond of my hair, which still doesn’t have a lick of gray, and I would prefer my real friends, if I actually had any real friends (most of my friends were her friends, and since she has more influence and money, their friendship was an illusion that I bought into), to refer to me in the positive.

I know they say that people who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it. That’s probably why my life has been one continuous loop-de-loop. My love life especially has been a continuum of superficial disasters, and overly dramatic bottle rockets that shoot up into the ether with spectacular promise and then repeatedly go poof, leaving nothing but a wisp of smoke and the inevitable question, “Is that it?”

I stopped walking. Standing on the Avenue of the Americas, people shoving past, I felt I couldn’t walk and think at the same time. This blistering moment of self-awareness tightened in my chest like a premature heart attack. I couldn’t breathe. I wanted someone, anyone, to grab me and shake me. Or hug me. But that wasn’t going to happen. I needed to suffer through this which, looking back, at least explains the insanity of what I was about to do. There just wasn’t enough blood going to my brain.

I was ordered out of my wife’s apartment and had no luck finding anything I could afford that I would want to live in. The few Benjamins coming from the severance didn’t provide me with any comfort. And I couldn’t see taking a step back, moving into a single apartment near Greenwich or the Lower East Side and starting over. I couldn’t bear it. Fact was, I was a thirty-four-year-old, rudderless divorced man, who had been living an extended adolescence by the grace of his good looks and pothole-deep charm. And yes, I was crystal clear that most of my failures, and a good portion of my regrets, were my fault.

I’m not a victim. Just an idiot. And what I did next should prove that.

I hadn’t spoken to my brother in at least five months. He called on my birthday. Partially to remind me that I hadn’t called him on his, partially to wish me a good day. We no longer sent each other presents but we do try and call. Well, he does. Cody is like that. Organized, pragmatic, together. Pretty much the dutiful brother to my more hands-off approach to life. Three years my junior, Cody and I have little in common other than DNA. I always find it fascinating, two siblings, raised in the same home, same parents, generally the same upbringing, and yet so intrinsically polar. If Cody and I were continents, he’d be Europe: stately, historical, roguish, built to last, and I would be America: flashy, dominating, babyish, self-congratulatory. Growing up, I was acutely aware of the power in my smile and green eyes, Cody seemed completely oblivious as to what his looks could score him. I wanted the best from life, Cody wanted to be the best in life.

You’d think I’d know my brother better before acting so irrationally. But desperate times call for at least a little effort on my part. And Cody seemed safe. Since we had always been vastly different people and knew so little about each other’s present lives, he would be less apt to pass judgment. And my judgments about him had long since been formed.

Putting himself through college with a pole vaulting scholarship, Cody was the epitome of the artistic jock. You know, that soulful creature that looks like he could crush beer cans against his head but secretly understands the meaning of haikus. He played sports all through high school but excelled when it came to launching himself sixteen feet in the air and contorting his body over a stick before falling back to earth.

Me, I played no sports. The single thing I did excel at in high school was the debate team. Not that I was remarkably well-prepared or did much research on any topic, but I always scored afterwards with a girl from the opposing high school who usually fancied herself a future D.A. What was it about high school debate teams that attract girls with great racks? Maybe it was all the drama. Maybe it was the chance to show off their intelligence rather than their bodies. Maybe it was the opportunity to actually be right when arguing against a guy.

Thankfully, Cody was never the kind of little brother who followed me around wanting to hang out with me. I had friends whose little brothers were major pains in the ass, spying on them and then holding the petty crimes they witnessed over their older

sibling’s head. Not Cody. He marched to the beat of his own drummer. Or more accurately, his own bongo player. His worst habit, and this was something that brought him incredible piles of misery, was that he almost always told the truth. Unlike me who

never met a lie he didn’t like, Cody seemed incapable of covering his own ass. I shook my head in disbelief every time he got caught doing something. Easy lies would present themselves, staggering around like dying elephants waiting to be poached for their ivory, and he would blurt out a confession that wouldn’t have come out of me without a severe beating. I used to believe there was something wrong with him, like he was missing the self-survival chromosome. Or maybe there was only so much of it in our family and I hogged it all. All I could figure was that he had a masochistic streak that ran deeper than the creek behind our house, or that he enjoyed the attention it brought him by coming clean. But later I discovered that all this truth-telling changed something in him as he aged. He committed fewer stupid errors. Always fessing up to his blunders kept Cody on the straight and narrow.

Why bother doing something stupid when you’re just going to rat yourself out?

This dented our already distant relationship. How could you not hate a guy who seldom did anything wrong, and when he did, readily admitted it? Back then we had a name for people like that: dumbshit. But I knew this anti-adolescent behavior would catch up with him. Sooner or later, never experiencing the kind of well-honed, deliberate, and often dangerous, trouble that most teenagers relished (and then denied to their parents) would curse him.

But Cody’s on-coming train wreck of a mistake was hilariously colossal next to the litany of asinine stunts I pulled. His admittance only iced the cake.

I was in my sophomore year in college. I’d gotten accepted to the University of Virginia. Don’t ask me how. My SATs were pretty good. Again, don’t ask me how. I remember guessing on most of the questions, trying to find a visual pattern in the answers and sticking to that format on what I didn’t know. Which was pretty much everything. Seemed to work more than it didn’t, much to the joy of my parents who then accused me of not applying myself more during high school. As I walked my parents back to the Plymouth after we unloaded my things into my college dorm room, my mother sniffling, not from sadness but from a late summer cold, my father turned and took me by the shoulders. I’d never seen a prouder look in his eye when he gave me one of the few pieces of advice he ever bestowed on either of his sons.

“Please don’t embarrass us.”

The phone rang early one morning. Since I never signed up for a class before noon, early could have been 11:45 but whatever it was, I was still in bed and hung over from another night of whiskey shots and beer chasers. It was my mother on the other end of the phone. She was sobbing. Inconsolably.

“Is it Dad? Is he dead? Did Cody finally kill himself pole vaulting? Do we have insurance on him?” I quizzed her coming out of my stupor.

She bawled into the phone for another moment before she finally pushed out, “You need to talk to your brother.”

“He did hurt himself and blew his chance at a college scholarship,” I railed. “I knew that peckerhead would eventually get an arm or a leg ripped off. He’s not touching my college fund. You guys put that money in there for me. He was supposed to get a scholarship. If he hurt himself that’s his fault, let him go to trade school or something. He can’t touch that money, it’s mine.”

I was nothing if not benevolent.

My mother continued to cry. There is nothing worse in the world than hearing your mother sob, except perhaps hearing your father blubber. Finally, through her heaving and sighing, I gathered that my mother had returned from grocery shopping to

find Cody in his bedroom with Tim Deverman, the captain of the wrestling team. Tim, all 215 muscled pounds of him, was naked, his face buried between Cody’s legs. Now for a woman who, bless her sheltered soul, was the chairperson of the Saint Martin’s Catholic Church Winter Bazaar and Raffle, this was something that I’m sure at first made no sense. She had no frame of reference. Was Tim searching for a lost contact in Cody’s chair? Had Cody passed out with Tim trying to revive him? Was this some sort of new exercise? But the give-away was when her own son, his T-shirt pulled up over his chest, his pants around his ankles, his eyes rolled back in his head, growled repeatedly “Yeah Tim, that’s it, take it…”

There are certain signals even your mother catches.

She slipped back out of the room without “the boys” noticing, returning to her kitchen in a state of denial and put away her groceries, making sure the labels on all the cans faced front. An hour later, Cody and Tim bounced down the stairs into the kitchen announcing they were starving as they dove into the refrigerator to find whatever was quickly edible. My mother said nothing. After Tim wished her a good afternoon and told Cody that he would see him in class the next day, Cody strolled past Mom and kissed her on the cheek, saying he loved her.

What caught his eye is that Mom wiped the kiss off her cheek with the back of her hand. He stopped, taking a hard look at her. She was wan, her face the color of Cream of Rice.

“You okay?”

Mom, being Mom, which means the queen of avoidance, nodded silently. Cody knew that meant something serious was on her mind. We had memorized all her signals since she never mastered the art of verbal discourse, even with her kids.

“Mom, tell me,” Cody pleaded, able to see that whatever had rendered her mute was severe.

Mom just pointed upstairs and began to sob.

Cody knew immediately. He took her in his arms and held her as she cried, explaining to her that he was gay. Mom was shocked. Besides the fact she didn’t know a single other gay person, her son showed no signs of being a stock-in-trade homosexual.

Even I have to say, I was a little taken aback when she told me. Cody was a jock, a man’s man, and I say that with no irony. He was muscled, slyly handsome, had a deep, coarse voice that sounded like someone grinding stone. Mom would have no clue, even though I should have put it together since he never had a steady girlfriend in high school even though a majority of the girls at Kennedy High were falling all over themselves to go out with him or get under him. I had heard that unlike me, whenever Cody was on a date, he behaved like a gentleman. Let me tell you now, any time the word “gentleman” is associated with a hormonally-obsessed teenage boy it means he’s a homo. Case closed. Come to think of it, Cody never did talk much about his conquests. Me, you couldn’t shut up.

All I could say to my Mom was, “Well, it could be worse. He could be doing the captain of the chess team. How fucked up would that be?”

She didn’t laugh. Being tickled by my sarcasm was never one of my mother’s strong suits.

I reasoned with Cody against coming out. Since Mom knew, Cody figured, rightfully so, that Dad would soon find out. My parents weren’t the kind of people who were going to disown their own son. That kind of behavior is saved for religious nut jobs who believe the Bible talks to them and only them in special ways. Such as my Aunt Carol, who told Cody at his high school graduation party that he was going to hell.

“It says right there in Leviticus that homosexuality is an abomination,” she stated as she handed him his graduation card with twenty dollars inside.

Cody smiled, patted Aunt Carol on the shoulder and said, “Did you know that the same arcane passage in Leviticus condemns the eating of shellfish? But that doesn’t stop you from stuffing yourself into a booth at Red Lobster for all-you-can-eat shrimp, now does it?”

Even though I can’t wrap my head around the whole gay thing when there are so many more fun parts on a woman, you had to admire Cody for remarks like that.

My parents, rest their souls, adored Cody. And not just because he saved them tens of thousands of dollars by getting a four-year free ride to college. But mainly because he was the antithesis of me. He was a star athlete on his way to Arizona State on a track scholarship. His grades were always in the top five percentile nationally and he treated my parents with love and respect. Again, I should have known he was gay. When you overachieve that much, you’re compensating for something.

I begged Cody for the sake of our folks not to make any public pronouncements about his sexual orientation. Just because the hard part was over, having his parents discover his secret, there were still a lot of hazards on the horizon. I convinced Cody that there would be a lot of people, especially those he’d been sharing a shower with at the high school, who wouldn’t cotton to discovering the man they’ve been lathering up next to actually enjoyed it.

“If someone bashes you in the head with a lead pipe and turns you into a drooling quadriplegic it’s going to be real hard to collect on that pole vaulting scholarship,” I warned him before suggesting he just keep discretely messing with the captain of the wrestling team but avoid taking him to the prom.

I never heard much about Cody’s sexual proclivities while he was in college. My Mom and Dad would call me and brag about how well he was doing in pole vaulting. What we didn’t know was that my brother met grad student Rhett Taylor-Richmond his junior year and moved into Rhett’s apartment while keeping a room at the dorms, which he used only when my parents came for their yearly campus visit.

Rhett Taylor-Richmond was exactly what his name flagrantly announced, a Southern, monied, poof. Rhett was at Arizona State studying photography and filmmaking. He also modeled part-time. I’ll give Cody credit, he never seemed to attract less than stellar beaus. Like my brother, Rhett was a true adrenalin junkie, with an addiction to the overtly dangerous. Rhett once snatched up a poisonous adder with his bare hands and explained how if this very pissed off creature bit him he would fall to the ground with excruciating spasms and slowly suffocate on his own phlegm.

This guy was perfect for my brother.

After Cody graduated, he entered an interior design program, on Rhett’s dime while Rhett disappeared into the Venezuelan wilderness to shoot his first documentary on a tiny tribe of indigenous Indians, the Cuocma, who worshipped scorpions as the descendants of Mozata, their earth spirit. Dying from a scorpion sting meant you were blessed and would enter the afterlife. Not dying from a sting meant you were possessed by evil spirits and you were summarily beheaded. Sort of screwed if you do and screwed more if you don’t. Not a surprise the tribe is near extinction.

Believe it or not, the film won three prestigious film festival awards and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary. I caught a glimpse of my brother and Rhett at the ceremony walking down the red carpet behind some very fuckable blonde starlet from some action flick who was posing for the paparazzi. Rhett’s film lost to a documentary about a retarded man who won the lottery and subsequently lost all his money at the hands of bad investors but nonetheless maintained a positive attitude because he was a winner and they couldn’t take that away from him.

I’d rather have the cash.

Cody and Rhett fell deeply in love – another ability besides jumping over a very high pole that my brother has which I lack – and held a sunset “union celebration” on a west-facing mesa in the Arizona desert outside Flagstaff, where I was one of the groomsmen. My parents came with their video camera and shot the whole affair, though I don’t believe they ever showed it to anyone back in Virginia.

Anyway, I can’t say what exactly overcame me that I dialed Cody’s number. He and Rhett resided in some spectacular house they built in the dawn-fogged hills of Sonoma, California. Wine country. The home was equipped with its own mini-film studio full of state-of-the-art equipment that being a documentary filmmaker doesn’t allow one to afford, but being a trust-fund baby does. Cody also had his interior design office in another part of the fifty-six-hundred-square-foot, two-story, Spanish-coast inspired home. Cody had become both well known and sought after in the world of environmental design and decorating. He traveled more than Rhett, though not for as extensive periods of time. My little brother was now successful and more sickening, personally wealthy in his own right. Cody and Rhett were a Marin/San Francisco power couple, the kind that didn’t throw parties but rather held charity fundraisers. Recently, they had adopted two children, a brother and sister, from Cambodia after Rhett spent a few months there in an attempt to document the migratory patterns of some nearly-extinct amphibian, sleeping on the jungle floor, all the while fighting off some kind of pango-pango disease he got eating a local dish, pa-toi, which he found out was later was made from the intestines of river rat.

You eat river rat in any form, you deserve what you get.

So on top of now being a successful, photogenic, gay power couple, they were raising two orphaned Asian children. Does this picture get any more perfect? Maybe if one of them in their spare time could solve the riddle of HIV they would really be onto something.

“Happy birthday,” I said when Cody answered his phone.

“It’s not my birthday. Not even close,” he responded in his deep bass voice that sounded like he eats mere mortals for breakfast.

“Consider me early.”

“I’ll consider you four months late from my last birthday,” Cody stated. “How are you, Conner? I heard the bad news about you and —”

“Don’t say her name,” I demanded.

“Why?”

“Principle.”

“That’s childish,” Cody stated.

“Welcome to my world,” I responded. “And since it’s mine, I can be anything I want to be. So, I heard you and Clark Gable adopted a couple of refugees.”

“I hate when you call him Clark Gable. Rhett hates his name enough. And our kids aren’t refugees. Trevor and Claire were orphaned.”

“Trevor and Claire? Excuse me, but you named two kids with jet-black hair, yellow skin, and slanted eyes, Trevor and Claire? Are you out of your mind?”

“Worse,” Cody boomed through a laugh, “their full names are Trevor and Claire Taylor-Richmond Carter.”

“Sounds like a legal firm.”

“We’re hoping that at least one of them takes up law. As long as it’s in the area of social justice.”

“Stop already. God, I hate the nobility of the rich. Be thrilled if they grow up not to hate you.”

There was a silence. That was Cody’s method of shifting into a more serious mode. He would stop speaking for a moment as a way to announce that what was coming next would be more earnest in intent.

“Are you unhappy, Conner?”

Intuitive.

“As matter of fact, Cody, yes. Yes I am.”

“What’s your next step?” Cody asked with an almost therapeutic tone that I immediately resented.

“If I knew that, I wouldn’t be on the phone with you about to ask the most insane thing that’s come to my mind since the divorce. And trust me there have been a lot of deranged thoughts lately.”

“Do you need money?”

“No. Well, yeah, a few million would be great. But for right now, how would you like a house guest?”

Again silence. That dragged on just a little too long.

“Forget it,” I blurted out, stung, not willing to subject myself to a lecture or worse, more silence, “I told you it was a very bad idea.”

“No, no, let me respond,” Cody demanded. “You asked if I wanted a house guest. The answer is no, I would not like a house guest—.”

“Goddamn, you have to learn to control that annoying honesty.”

“Would you let me finish? Rhett is busy finishing up funding and travel plans for his next project, and I am up to my ears in work. And with Trevor and Claire, who don’t even speak English, it’s mayhem around here. I’m not sure you would enjoy yourself much. I wouldn’t have a lot of time to spend with you. And I wouldn’t have a lot of time to listen to your problems.”

“Like I would share them with you,” I shot back.

“They’re apparent, Conner,” Cody replied with enough snark in his voice to let me know he was smiling when he said it. “It’s just that now the kids come first. I’m not saying you can’t come, you’re welcome to stay as long as you need, I’m saying be prepared.”

“Do you have a spare bedroom?”

“We have three spare bedrooms and a guest apartment,” he responded, sounding damn right apologetic. “I know it’s a lot but we may adopt again. Rhett and I have been blessed. We feel we should give back.”

“Good. Then give some to me,” I said with enough sarcasm to let Cody believe I thought he should be embarrassed by such excess. “I’ll take the guest apartment, that way I won’t be in the way.”

“You’ll stay in a bedroom. The guest apartment is reserved for the housekeeper-slash-nanny we’re trying to hire if we can ever find someone we trust.”

“I’m sure I’m not on that list,” I replied.

Cody’s laughter came from too deep in his gut not to be insulting.

“You can have the guest room overlooking the garden. There’s a small breakfast bar, with a microwave and refrigerator in the room. So if you subside on pizza rolls and beer, you never have to come out of the room.”

“Perfect. I don’t like the daylight hours much anyway.”

“Glad to know things haven’t changed. See you when you get here.”

When I hung up, I wondered if I was truly certifiable. What would I do in a house with two overachieving homos and two kids who don’t speak the language? If I hadn’t been driven to drink through my divorce, well, drink more than I already do, this could very well shove me right over the edge. I know it might seem really great for someone whose little brother hasn’t far outshined them; a beautiful house in wine country, my own room with a little kitchen, overlooking a garden no less. But I was hiding. Pouring myself deeper into an alien environment so I wouldn’t have to face where I was in my life.

I hardly knew Rhett. I’d been around him maybe a grand total of four or five days and spoken to him on the phone a time or two more than that. For that matter, I didn’t really know my brother well either. I more knew of him than actually knew him. Only an utterly desperate man would to do this.

Oh yeah, that’s right. I was.

I needed to convince myself that this was a good idea. That it would be a great place for me to get my head together and refocus my life. But the gurgling in my gut reminded me that it was neither. Hard fact was I had nowhere else to go. Cody’s was as far away from New York as I could get and still cost me nothing more than a plane ticket and rental car.

I’ve only cried maybe five times in my whole life. And three of those were when my father whipped my ass. The other two were when my Grandmother died and when our dog, Gilligan, got hit by a car. I certainly felt like it now. Not for the reason you might suspect though. If I were an optimist, this would be my time to start over, begin the second act of my life. But I wasn’t an optimist. I wasn’t a pessimist either. Nor a realist or dreamer. I never gave much thought to anything. And in that was the crux of the biggest problem in my life. I’d never developed anything, good, bad, up, down, this way or that, which would define me as a person. I’d never taken a stand on anything, never made a decision that made a real difference, never swung for the fences, never took a step where there wasn’t an escape route. Whichever path was greased, I slid down it like a six-year-old on a banister. I never challenged myself. I never felt much pain.

And quite honestly, even the pleasure of which I was a seeker, was never monumental.

I no longer had the ability to laugh until I cried because nothing affected me strongly enough. I never declared ownership over the bad things that I did. I never felt their wrath. Even my marriage ending and losing my job registered to me only as disappointments, rather than the personal life failures they truly were. I never invested enough in them for either to cause me to ache when they were lost. For thirty-four years I willingly refused to develop my own person so I could fit into any place, any situation, and assume the role I was assigned to play.

What was worse than being thirty-four when I finally figure this out? Being thirty-four and having no idea how to change it. I felt like I was within days of becoming invisible. I would step out onto a busy New York street, disappear into the crowd and never be seen again.